Business analysts generally have a handful of change initiatives on the go at any one time. If we’re lucky, we’re able to manage the peaks and troughs of demand between them, so we’re neither over-worked nor twiddling our thumbs.

To ensure we’re effectively utilised – and so change initiatives are delivered in timely fashion – we need to plan our work in advance.

Planning your work effectively brings a host of benefits:

- Helps you build and maintain good relationships with colleagues and stakeholders

- Helps your Project Manager

- Demonstrates professionalism – helping the BA brand!

- Helps you manage your workload across multiple change initiatives

- Enables you to respond to unforeseen events more effectively

Good planning requires a fair bit of thought. In this post, I’ll talk through the steps you can follow to create a workable plan.

How do I work out what activities to include?

Think about the overall service you’re providing. Are you defining the problem? Improving a business process? Engineering requirements?

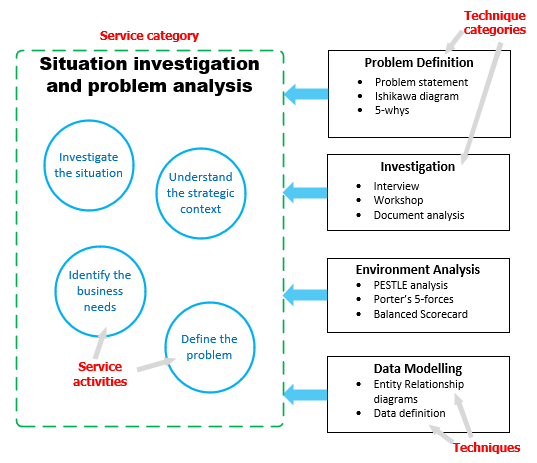

Different services tend to involve different sets of business analysis techniques. Service Frameworks can be a great way to explore and understand the connections between services and techniques.

Debra Paul and Christina Lovelock’s book Delivering Business Analysis provides a great example of a BA Service Framework. High-level service categories (e.g. “feasibility assessment and business case development”) contain activities (e.g. “evaluate alignment of options with strategic goals”) and are then matched to technique categories (such as “environment analysis”). A framework like this enables you to drill-down from overall aims to specific techniques you might employ at any stage of a change initiative.

I’ve attempted to illustrate this below.

Every change initiative is different, and you’ll need to tailor activities as the context demands. For example, in a project where stakeholders are spread across several countries and time-zones, questionnaires may be more appropriate than workshops.

How can I estimate my effort for an activity?

Your plan should show how much time you will spending on activities. This will help with establishing the overall costs of the change initiative. It’s also used to establish your utilisation and availability for handling other change initiatives simultaneously.

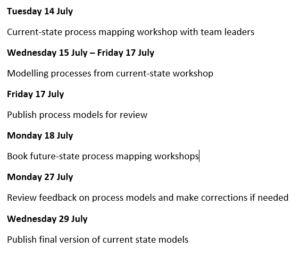

To figure out the effort required for a given activity, try breaking it down into smaller chunks and estimating those. For example, running a process modelling workshop might include the following:

- Preparation

- Running the workshop

- Modelling

- Sharing outputs and validation

- Corrections and publishing

For each chunk, think about whether it’s likely to be less than an hour, half a day, or a full day. Anything longer than a day might benefit from breaking down into multiple activities.

Think about the scale of what you’re dealing looking at. How many processes? How many stakeholder groups? Will you need to run multiple sessions to cover all the relevant people?

Consider whether you’ve performed the activity before, and whether this is likely to be similar. Perhaps talk to other BAs about their experiences.

It can be helpful to consider best and worst-case scenarios, and how likely you feel they are.

What about how long things will take in practice?

If we only had to worry about our own effort, business analysis would always be finished pretty quickly! In practice, our activities tend to be spread over days, weeks or even months!

Typically, we are dependent on the availability and input of our stakeholders. If possible, investigate whether stakeholders will be available when you need them. Consider their day-jobs and ensure you’re not being overly optimistic about how much time they can spare you.

Explore any constraints – is a key stakeholder only available on a particular day each week? Do meeting rooms hold a maximum of eight people? Are there particular protocols that must be followed?

Think about any external factors that might affect things – will you be waiting on decisions from outside the project? Are you dependent on a budget cycle? Are key resources going to be busy elsewhere? How does your own availability and commitment to other change initiatives affect things?

How do I turn it all into a plan?

Consider any dependencies between activities. Can you progress things in parallel. Does an activity have to wait until something else is completed? This can help you build a logical order for the activities you’ve identified.

You can then factor in anything you’ve discovered about your stakeholder availability or other constraints so you can start to build up a timeline with some real dates.

You can document your plan in Word, Excel, MS Project or any number of planning tools – your organisation may require a formal plan submission, or you might just be keeping a document for your own purposes.

Make sure you document any assumptions you’ve made along the way.

If you’re sharing your plan with others, it can often be worth highlighting your level of confidence, or any particular risk points you’ve identified that may cause the plan to change dramatically.

It’s always worth talking to a project manager! PMs are experts in creating work breakdown structures for project plans and can advise whether you are looking at an appropriate level of detail.

The further away things are, the less certain we can be about them. It’s rarely worth trying to nail every detail of a plan over a period of several months. Instead, flesh things out at greater levels of detail as they get closer. You don’t need to know that you’ve got a 2-day workshop next January, but you do need to know you’re in Manchester on Thursday!

And once I have a plan..?

If you’re working alongside a project manager, they’ll probably want to incorporate your plan into the overall project plan.

Make sure your stakeholders know when you expect them to be involved. Give them as much warning as possible – and keep warning them! It can be helpful for them to see what else is in your plan so they can see the impact of any changes you need to make.

Keep the plan under review as you progress and add more detail as things get closer.

There are always going to be unforeseen events that throw curveballs at your plan! But because you have a plan, it’s much easier to identify any impacts, adjust things accordingly, and work with your colleagues and stakeholders to handle things.

It’s always worth reviewing the plans you made when you reach the end of a change initiative. You can assess whether you were accurate in your estimates or made incorrect assumptions about whether key resources would be available. Build these into any lessons-learned activities so you can benefit from what you discovered in future initiatives.