Like most business analysts, I’ve worked on plenty of projects in my career that should probably not have been given a green light. Some of these went on for many, many months, with all those involved feeling powerless to stop them. In this post, I’ll look at how organisations end up pursuing the wrong projects and change initiatives.

A project is “wrong” if it doesn’t deliver on the organisation’s strategic goals. Running the wrong projects can spell disaster for an organisation, bringing a host of negative impacts:

- Wasting money and resources

- Negatively affecting customers

- Negatively impacting business operations

- Reducing stakeholder buy-in for future initiatives

- Losing out to competitors that made better decisions

- Failing to achieve the benefits of delivering the right projects instead

- Creating a culture of blame and mistrust

- Destroying staff morale and reducing the ability to attract and retain talent

- Risking reputational damage

- Creating additional obstacles to achieving the organisation’s strategic goals

It sounds pretty obvious that organisations would want to avoid pursuing the wrong projects, and yet it happens time and time again.

How does it happen?

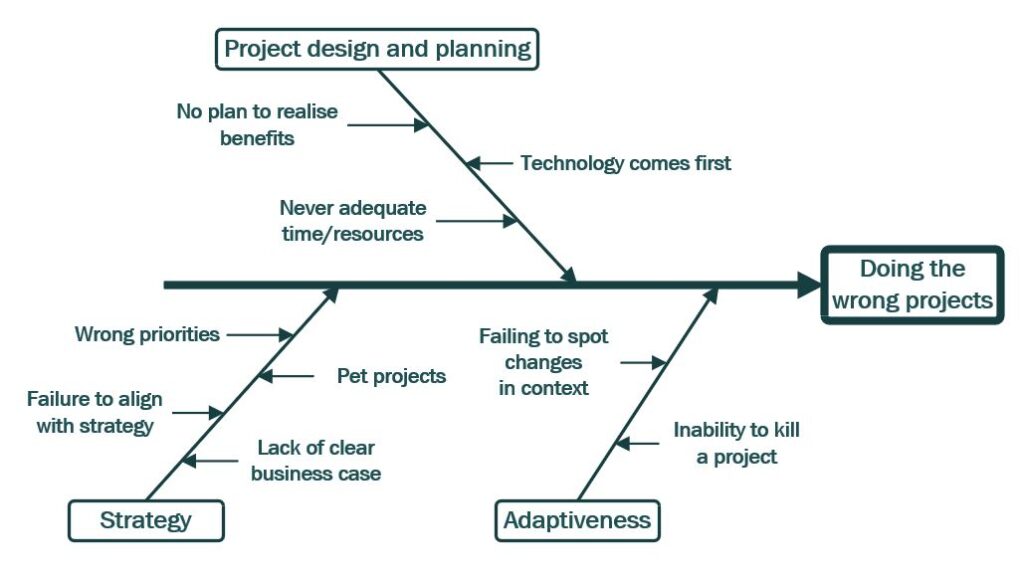

The reasons for pursuing the wrong projects can be grouped under 3 main categories:

- Strategic errors

- Project design and planning failures

- Failure to adapt

1 – Strategy

Failure to align with strategy

It’s amazing how often senior managers can have wildly differing views on what their organisation’s strategic goals are.

Often, they may have competing targets and objectives resulting in them pulling in conflicting directions. This means that projects can end up being approved by whoever shouts loudest, and the organisation’s efforts and resources are steered off in the wrong direction.

It should be possible to draw a clear “golden thread” from the organisation’s goals to the projects being delivered.

Poor prioritisation

It can be really disheartening for staff to work really hard on a project only to discover that something else should really have been the company’s focus. A great idea can end up being the wrong project if the timing is wrong or something else needs to come first.

In some organisations, projects only get a green-light if there is a business case demonstrating a strong financial return on the investment – either through increased revenue or a reduction in costs. While these might be perfectly sensible aims, it can mean that projects bringing other types of value never get approved – those that improve customer experience, improve conditions for staff, or future improve sustainability.

Prioritisation of change portfolio is a complex activity; it requires clear articulation of needs, dependencies, strategy, resource availability and risk appetite. Things get even harder when projects may bring different types of value (cost savings, value to customers, competitive advantage etc.).

Whoever oversees the organisation’s change portfolio needs timely and accurate information about initiatives (both in-pipeline and in-progress) and about the strategic goals and objectives.

Enabling pet projects

Senior stakeholders with a budget to spend (or simply the power to get their way) can often get their pet project initiated, jumping queues and monopolising resources. At least one other factor from this list will usually be in the picture as well.

As the sponsor has so much power – and so much at stake – it can become impossible to prevent the project being launched, or to kill the project if things unravel.

Lack of clear business case

I’m often staggered by the ease with which millions of pounds can be made available for projects with flimsy business cases. In some cases, expense claims get more scrutiny.

If the costs and benefits of undertaking a change can’t be articulated, there is a real risk of wasting effort and resources.

Not everything needs to have a direct monetary return on investment – there are plenty of other kinds of business benefit – but if a project is to go ahead, it needs to be obvious what the benefits will be, when they’ll be realised, and the likely costs of obtaining them.

Even where a business case is presented for approval and looks on paper to be sound, if it isn’t scrutinised appropriately (and from multiple angles) then there is still a risk of green-lighting a project in error.

2 – Project design and planning

The technology comes first

When an organisation has to change to fit the technology, it’s often a recipe for disaster. This can often happen with business critical systems – CRM, finance, document management – and the project scope often consists of just getting the system up and running.

A project may be born out of a senior stakeholder seeing a system they like elsewhere (perhaps in their previous company or at a competitor), or from viewing the driver for change through the lens of deficiencies in an existing system.

It’s not uncommon for business analyst job adverts to ask for experience with a particular technology platform (such as Sage, Microsoft Dynamics, or SharePoint), and this can be a clue that that the project is seen primarily as an IT change rather than about solving business problems.

Inadequate time or resources

Projects can get initiated without adequate time or resources committed to deliver all the required changes. As any project manager worth their salt will tell you, if time and cost are fixed, the only thing that can move is quality. The project may finish on time and on-budget, but it will never deliver the expected value.

This is a waste of time – if you can’t find the time or resources to deliver your project, you need to do something else. That might mean defining a smaller, less ambitious project, or focussing your efforts on something else entirely. Your organisation’s strategic goals are not going to fulfil themselves if the organisation is pursuing ineffective projects!

No plan to realise the benefits

This happens most often with projects where the business case rests on “efficiency savings”.

There may be a host of calculations demonstrating that the project will save X headcount, but if there’s no plan in place to actually deliver those savings (and commitment to it from relevant management), it never ends up happening. In particular, look out for projects that will save a small amount of time for a large number of staff – these time savings will ultimately just be absorbed by other activities.

If it’s not obvious from the business case when the benefits will be realised, how this will happen, and who is accountable, then it’s highly likely the project will fail to bring about much benefit at all.

3 – Adaptiveness

Failing to spot changes in context

Large projects and programmes require massive mobilisation of resources, planning over months or years, and are generally a huge commitment for any organisation. While a project is being delivered, the external contexts can change rapidly. New regulation can be brought in. Better technology is created. Customers’ wants and needs shift. Competitors compete. Meanwhile, the internal environment also shifts continuously as other change initiatives are delivered and business objectives pursued.

The risk and opportunity landscapes are always evolving. Failure to put in place effective risk and opportunity management processes means the right project can rapidly become the wrong project, so responding quickly to change is essential!

The larger the project or programme, the larger its turning circle. Even if the organisation is able to identify changes to the project’s wider context, it can be almost impossible to change direction or even to stop the project – despite it becoming obvious to everyone that the deliverables won’t be fit for purpose or that resources should be focussed elsewhere to capitalise on opportunities or respond to risks!

Inability to kill a project

A project’s business case is rarely re-examined during delivery. It can be as if everyone has chosen to live by David Brent’s immortal words “a good idea is a good idea forever”.

Many projects just seem to rumble on for weeks and months after it’s obvious to everyone that it should be cancelled. A project manager is rarely empowered (or incentivised!) to put their head above the parapet and say “we should look at ending this”. A business analyst – who may have written the business case – is now tasked only with requirements engineering, or facilitating UAT. The sponsor may be too invested to countenance stopping things.

If an organisation doesn’t recognise the value of stopping a doomed project – and put in place mechanisms to encourage this – it will keep making the same mistakes.

Summing up

The most important project and programme decisions will be made by the most senior people in an organisation. It can actually become less likely that business analysis will be applied to the most critical decision-making. This is a particular issue in organisations where BAs are seen as purely a project delivery resource, rather than professionals offering a range of services to support strategic delivery.

It’s not all doom and gloom! In Part Two, I’ll look at the approaches organisations can adopt to avoid these pitfalls. Spoiler alert – business analysis features prominently in the solutions!

Great article Stu – very true. Looking forward to your thoughts on how to avoid these pitfalls!

Comments are closed.